The strength training community is obsessed with categorization. From sumo pullers to “snatch specialists,” athletes that work with the barbell seem to adore applying labels and fitting themselves into neat, tidy boxes.

As such, you’ve probably heard in passing — or worse yet, been told to your face in the gym from an unwelcome do-gooder — that you’re “a knee-dominant squatter” or something of the like.

Before you can partake in the knee-versus-hip debate, you need to understand it. Is there such a thing as being a hip-dominant squatter, or a deadlifter who relies on their knees too much? Are these labels even useful, or just more meaningless gym jargon?

These are the ABC’s of the hip and knee, and what they mean for you.

- What Is Hip Dominance?

- What Is Knee Dominance?

- What Determines Hip or Knee Dominance?

- Best Exercises for Hip-Dominant Lifters

- Best Exercises for Knee-Dominant Lifters

Editor’s Note: The content on BarBend is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t take the place of advice and/or supervision from a medical professional. While many of our contributors and experts have respected certifications and degrees, and while some are certified medical professionals, the opinions and articles on this site are not intended for use as diagnosis and/or treatment of health problems.

(Very) Basic Biomechanics

The human body is unbelievably intricate. Just when you think you have a grasp on something pertaining to anatomy or physiology, there’s another layer to peel back and deepen (or muddle) your understanding of how you work.

On the flipside, biomechanics can be quite easy to get your head around. Although your musculoskeletal system is biologically complex, from a practical perspective, you can think of your muscles and joints as a lever-and-pulley system.

Your muscles, ligaments, and joints all obey simple physics. You don’t need a biology textbook to understand your performance in the gym — you’re simply a well-designed organic machine.

It’s also worth pointing out that the hip vs. knee conversation largely if not entirely revolves around how you perform squats and deadlifts (as well as their variations).

What Is Hip Dominance?

A hip-dominant lifter is someone who relies predominantly on the muscles in their hips or lower back to successfully make their lifts. That’s all there is to it.

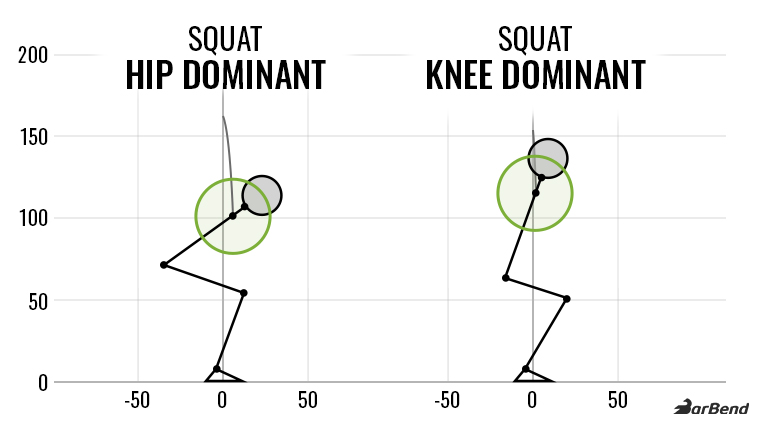

Hip Dominance in the Squat

The hallmark of a hip-dominant squat is torso angle. If you naturally — or, despite your best efforts — fold over while descending or ascending during a squat, you may be a hip-dominant athlete.

Any type of squat you perform in the gym requires that you perform two biomechanical actions: extension of the knee and hip joints. From a standing position, you can flex your knee or tip over at the waist and the barbell will descend in space.

[Related: The Best Strength Athletes in 2021]

Therefore, there’s plenty of leeway and variability to how you physically lower the bar. Hip-dominant squatters tend to rely less on forward knee travel, instead opting to push their butt back, lean forward, and compress into a more folded-over position when they squat.

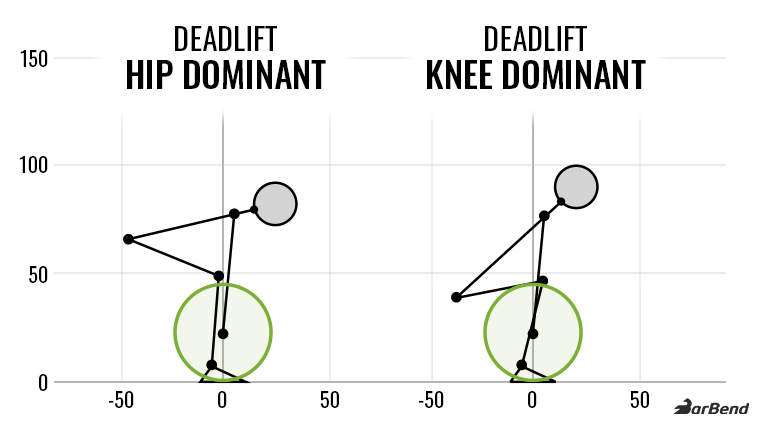

Hip Dominance in the Deadlift

The deadlift is somewhat less susceptible to variability. Since the bar begins on the floor and your task is to stand up with it as efficiently as possible, all deadlifts are completed via hip extension. There’s no getting around it.

To call yourself a “hip-dominant deadlifter” is like saying you’re an “elbow-dominant curler,” which isn’t saying much at all. You’re supposed to feel the deadlift in your hamstrings, glutes, and lower back (to a degree).

However, pulling style does come into play. The technique of the sumo deadlift naturally creates a more upright torso and more bent knees, so it is important to recognize that conventional pulling is usually more hip-dominant by design.

That said, segment length (how long or short your bones are) does affect just how much of that load is placed on your posterior chain. Athletes with shorter femurs may not need to pull with their hips as high or their torsos as inclined as a long-legged lifter.

What Is Knee Dominance?

Knee-dominant athletes, whether they intend to or not, lean heavily on their quads to do a lion’s share of the work in the squat and bear as much load as possible in the deadlift.

Knee Dominance in the Squat

When you squat, your knees flex and travel forward (to massively varying degrees depending on the athlete) while your hips fold and move both backward and down. An athlete who displays a lot of knee compression and forward travel with a more upright torso would be considered a knee-dominant squatter.

Interestingly, “knee-dominant squatting” is an effective moniker for a visual posture but says little about what actually happens with your lower body musculature.

[Related: Weight Categories & Competition Schedule for the 2024 Paris Olympics]

Plenty of scientific research has studied muscle activation during various types of squats, and much of it has arrived at the conclusion that your torso angle hardly affects how hard your quads, hamstrings, or glutes work. (1)(2)

Some literature does show higher quadriceps engagement in the front squat when compared against a “hip-dominant” movement like the low bar squat. But, broadly speaking, the major factor determining what parts of your legs work the hardest is total range of motion.

Knee Dominance in the Deadlift

Deadlifts of all shapes and sizes are much more about hip work than knee travel. When you use a barbell, it’s quite hard to turn a deadlift into a quadriceps exercise, no matter how you tweak or fiddle with your technique.

There are a couple of situations where knee dominance may play into how you pull. If you find that you’re strong and fast off the floor but your bar speed slows down as you approach a standing position, you may have very strong quadriceps that allow you to forcefully initiate the lift.

Further, the sumo deadlift typically involves more leg work than its conventional cousin, simply due to the nature of the setup. Your hips and spine are in a poor mechanical position to move the barbell, making the first half of the sumo pull almost entirely about your quads.

What Determines Hip or Knee Dominance

If you’re wondering why all your squats look more like good mornings, or how some career powerlifters seem to pull heavy weights with nearly-vertical torsos, rest assured that, for most people, hip or knee dominance probably doesn’t matter very much.

That said, there’s no harm in diving into the “why” behind your movement habits.

Anatomical Structure

As a lifter, you’re essentially a fleshy construct: Levers and pulleys. Your individual anatomy reigns over how you move in the gym, whether with a barbell, kettlebell, or just your body weight.

This is why, try as you might, your squat and deadlift will never look exactly like that of your favorite powerlifter. They may serve as a useful visual guide, but you were each dealt very different hands long before you ever picked up your first barbell.

Femur Length

Segment length is far and away the most important factor in how you move through lower body exercises. Specifically, the length of your femur (the large bone in your thigh).

Athletes with shorter femurs will usually be more upright when they squat and deadlift. Longer-limbed lifters simply have more leg that can get in the way of their positions in the bottom of the squat or while setting up for a deadlift.

Ankle Flexibility

Ankle range of motion also plays into what joint “dominates” your lifting. When you squat, your knees and hips flex concurrently. For the knee joint, this means forward movement. But if you’ve got limited ankle mobility, your knees can only travel so far.

For the barbell to continue moving downward, something has to give. As a result, your hips will flex more and you’ll tip over further, making your squat more reliant on hip extension when you go to stand back up.

Torso Size

The length of your spine (and thus how long your torso is relative to your legs) also affects how you lift, especially in the deadlift. Your shoulders must be directly over the barbell when you pull, and your shoulders are attached to your trunk.

As such, lifters with longer torsos will naturally “sit down” more in their pulling stance to bring their shoulders back on top of the bar, while shorter-trunked athletes need to raise their hips more to get their shoulders directly on top of the bar. This inadvertently also places more load on the hips and lower back.

Training Habits

Which joint you rely most heavily on isn’t just determined by how your skeleton is put together. Your training behaviors and, more specifically, the sport or outcome you’re working towards, also guide your hand.

For example, an upright torso is critical to Olympic lifters who need to perform the snatch or clean & jerk. Not only is an upright, knees-forward posture encouraged in the competition lifts themselves, but weightlifters make the high bar and front squats a centerpiece of their accessory training.

The weightlifting deadlift also necessitates the athlete place their hips lower and more forward than most powerlifters would.

These choices aren’t in service of knee dominance unto itself, but it tends to come with the territory. On the other hand, powerlifters need to squat to a very specific depth for their sport.

For some, the path of least resistance to depth involves folding at the torso and using a lot of leverage from their hips to lift the most weight possible. More commonly, an athlete may simply have a stronger back relative to their legs — potentially creating the dreaded “squat-morning.”

As such, they won’t push their knees as far forward to involve their quads, instead opting to place a majority of the load on their hips since it gives them the best opportunity to make the lift.

Best Exercises for Hip-Dominant Lifters

You shouldn’t have gaps in your training. Shoring up weaknesses and ensuring that your body is equally developed (as much as possible, anyway) will help you lift better, get bigger, or run faster. Conversely, even if ultra-upright high bar squats look pretty to you, you probably shouldn’t go out of your way to become a knee-dominant athlete for its own sake.

But if your hips are noticeably stronger than your knees, you should probably dedicate some time to bringing up your quadriceps strength. However, you can’t head to the weight room and fix a problem with your lifting by lifting the same way you usually do.

Deficit Deadlift

The deadlift leans heavily on hip extension, true enough. That said, whether you pull sumo or conventional (or work with the trap bar), the first half of the movement comes largely from quad strength.

By standing on an elevated surface such as a wooden riser or weight plate, you have to sit lower into your setup to reach the bar. This means more knee flexion than you would normally have, which naturally encourages you to use your quads more off the floor and should translate well to your standard pull.

Belt Squat

The axial, or on-the-spine, loading of a free-weight squat is what gives you so much freedom of choice in how you move. By changing the orientation of the resistance, the belt squat takes away your ability to turn the squat into a hip hinge.

[Related: Elite Lifters Share Their Thoughts Before a 1-Rep Max]

Even if you don’t have a belt squat machine in your gym, a makeshift replacement with a dip belt and some plates (or even attaching yourself to a low cable tree) will do fine.

The physics of the belt squat pulls your pelvis straight down, which takes away your ability to shift your hips back or forward. This effectively forces you to balance out how you use your lower body while squatting.

Floating Snatch Deadlift

Even though Olympic lifters rely heavily on their quads, it’s totally possible to have a bit of an imbalance between your anterior and posterior extensors. You can build up your knee extension strength and practice your snatch technique at the same time by using a “floating” pull where you don’t let the barbell touch the ground between reps.

Floating pulls test your work ethic and pain tolerance more than you’d think. The bottom position, where the bar is suspended off the ground, places enormous load onto your quads. You’ll want to compress your knees so the bar touches the floor, and your task is to resist that urge by utilizing every ounce of your leg strength.

Best Exercises for Knee-Dominant Lifters

There isn’t much wrong with using your knees heavily in your lower body training. If you pull sumo and squat high bar, you probably have beastly quads already. That said, there’s no good excuse to neglect your posterior chain.

Kang Squat

Once you know the rules of squatting, you have some ground to gain by breaking them — properly. The Kang squat can be a highly effective exercise for posterior chain engagement if you know how to perform it.

More of a technical primer than a mainstay movement, Kang squats intentionally have you shoot your hips backward as you ascend. For knee-dominant squatters, this provides some extra stimulation to your hamstrings and lower back in a low-load scenario, while also priming your body to tolerate any errant movement that may occur during heavier sets.

Block (or Rack) Pull

Knee-dominant pullers are often strong off the floor in the deadlift but lose steam the higher the bar rises. To remedy this kind of weakness, you need to remove your strengths from the equation.

Pulling from an elevated surface places the bar around knee height to begin with — the same height at which your quadriceps stop most of their contribution to the deadlift. What’s left is a posture in which your hamstrings, glutes, and lower back are your only tools to move the weight.

Nordic Curl

Balancing your lower body isn’t all about shoring up weaknesses. It can also be about protecting your strengths. Lifters who rely heavily on their knees to squat or pull may need to balance out all that compression and loading with oppositional movement.

The Nordic curl is a fantastic movement for knee prehab and hamstring strength, and you don’t need any weight to do it. When you squat, your quadriceps control the rate at which your knee joint flexes.

Maintaining healthy joints is about balancing forces (and using the right amount of volume), so you need an exercise in which your hamstrings resist the rate at which your knee opens. The Nordic curl accomplishes just that.

Practical Takeaways

The physical nature of lifting weights is far more unique and intricate than it appears at a glance. There’s little sense, then, in trying to pack yourself into a tight box or assign yourself a category that defines your movement.

Is hip (or knee) dominance a real thing in the squat or deadlift? Visually speaking, sure. Physiologically? Not quite as much. Moreover, how you move with the barbell depends on why you’re lifting in the first place.

If you need to squat to a certain depth, it doesn’t really matter whether you rely more on forward knee travel or hip flexion as long as you’re able to lift the most amount of weight comfortably and sustainably.

On the other hand, if your sport or training goal necessitates a certain posture — like an extremely upright torso to clinch a 1-rep-max snatch — you should exercise in a way that facilitates that. Even at the risk of being labeled “too knee-dominant,” whatever that means.

Understanding your body can help you train better, but don’t get too lost in the weeds of movement and forget that you’re in the gym to train hard, lift safely, and have fun.

References

1. Yavuz, H. U., Erdağ, D., Amca, A. M., & Aritan, S. (2015). Kinematic and EMG activities during front and back squat variations in maximum loads. Journal of sports sciences, 33(10), 1058–1066.

2. Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 23(1), 284–292.

Featured Image: sportpoint / Shutterstock